Salam Alshareef ne travaille pas, ne conseille pas, ne possède pas de parts, ne reçoit pas de fonds d'une organisation qui pourrait tirer profit de cet article, et n'a déclaré aucune autre affiliation que son organisme de recherche.

Grenoble École de Management (GEM) apporte des fonds en tant que membre fondateur de The Conversation FR.

Voir les partenaires de The Conversation France

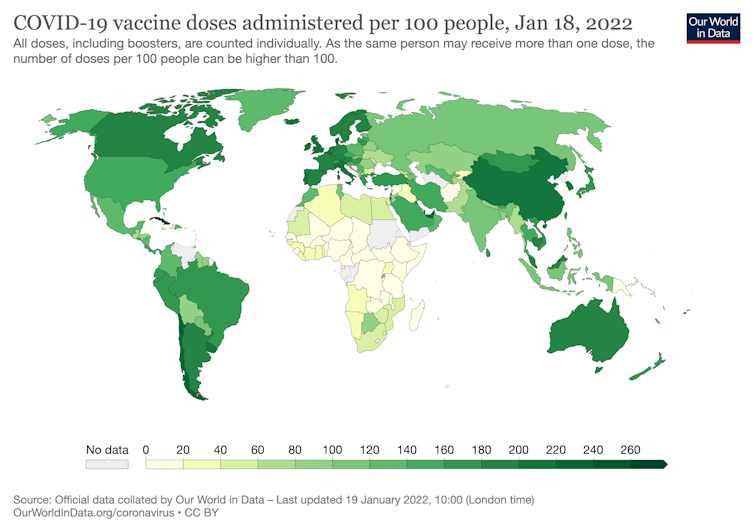

In an interconnected world, a pandemic can be overcome only when it is overcome everywhere – no one is safe until everyone is safe. Vaccination delays and supply shortages in protective equipment and treatments increase the possibility of the virus mutating. This undermines our ability to control the pandemic, even in highly vaccinated countries. And yet two years into the pandemic, vaccine doses are highly concentrated in rich countries.

As of October 2021, only 0.7% of all manufactured vaccine doses had gone to low-income countries. Manufacturers had delivered 47 times as many doses to high-income countries as they had to low-income countries.

Since its inception, COVAX, the UN-backed initiative dedicated to promoting access to Covid vaccines, has struggled to obtain doses. It recently passed the 1 billion doses delivered – half way to its goal of delivering 2 billion doses by the end of 2021. Indeed, AstraZeneca, Pfizer/BioNTech, Moderna, and Johnson & Johnson have delivered between 0% and 39% of their already inadequate commitments to COVAX in 2021.

The Global Commission for Post-Pandemic Policy, meanwhile, estimates that while Asia and Europe will be able to fully vaccinate 80% of their populations by March 2022 and North America by May 2022, Africa will not reach 80% at current rates until April 2025.

The unequal distribution of vaccines is partly due to insufficient production. This scarcity of supply is due to intellectual property rights, which give pharmaceutical companies a monopoly on production and exclusive rights to license their technology to other companies.

India and South Africa, co-sponsored by more than 100 other countries, initiated a campaign in the World Trade Organization to waive intellectual property rights to ensure the necessary production of vaccines, PPE, diagnostics, ventilators and medication. A waiver would ensure necessary production by allowing companies to produce Covid-related products.

Six months later, the United States surprisingly supported the waiver for vaccines, but not for other medical materials as advanced by the patent waiver initiative. Yet to date, Washington has not employed its political clout to apply the waiver globally, and Europe has refused the initiative.

Curiously, Brussels proposes to use the very flexibilities of Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights agreement (TRIPS), that it resisted and even undermined through its trade agreements. As Nobel Prize–winning economist Joseph Stiglitz argues these flexibilities are not helpful.

Intellectual property rights are political creature as they profit specific social interests and were lobbied for by them, especially the pharmaceutical, agrochemical, entertainment and media industries.

The signature of what is known as the TRIPS agreement at the World Trade Organization in 1994 was a historic turning point for intellectual property rights, and is today exacerbated by more stringent US and EU bilateral trade agreements.

These were key steps in the enforcement of “intellectual monopoly capitalism” which has transformed a world mainly based on open science into a world of closed science, and led to the concentration of knowledge into a few hands to an unprecedented degree.

The legal monopoly over knowledge, which extends well beyond national boundaries, enables owners of intellectual property rights (IPR) to exclude others from using new inventions, reduce competitive supply and increase prices. The control of IPRs is a central element in transnational corporation strategies of accumulating intangible assets to extract absolute rents.

In an increasingly financialised health sector, where the priority is to increase profits for creditors and shareholders, the accumulation of a portfolio of intellectual property rights allows for the extraction of monopoly profits.

In 2019, investment management corporations such as BlackRock, Vanguard, and State Street were the majority shareholders in firms involved in vaccine development including Pfizer (75.1%) and Johnson & Johnson (68.1%). This is problematic, as research shows that a key determinant of innovation in the health sector could become generating returns on investment, not protecting health.

Therefore, some economist argues that the global economic system is “structurally pathogenic”, with negative rather than positive impacts on human health.

A July 2021 analysis by the People’s Vaccine Alliance shows that Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna are charging governments as much as 41 billion US dollars above the estimated cost of production for vaccines. The EU, meanwhile, may have paid 31 billion euros more than the estimated cost for its mRNA doses.

The same analysis shows that countries are generally paying between 4 and 24 times more than they could be for Covid-19 vaccines. But a recent report by the consumer advocacy group Public Citizen suggests that setting up regional hubs to manufacture 8 billion doses in one year would cost about $23 billion for the Moderna vaccine, and $9.4 billion for the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine.

Put simply, without intellectual property monopolies, the money already spent by COVAX would have been enough to fully vaccinate the entire population of low-income and middle-income countries.

Moreover, citizens are paying the pharmaceutical industry twice: first because they are paying monopoly profit, and second because vaccines were developed with public funding through large subsidies for research and development, and through public pre-orders of vaccines.

The proponents of tight intellectual property rights argue that in their absence, inventions would be accessible to third parties without ensuring enough compensation for inventors, thus discouraging investment in innovation. But Joseph Stiglitz argues that there is no evidence supporting this mainstream view.

Indeed, intellectual property rights establish distorted incentives to create market power. Monopolists use their power to block innovators who endanger their dominant position, and try to maintain their position by getting only a little bit ahead of their rivals – which has an adverse effect on innovation.

This became clear during the Covid-19 pandemic. The New York Times reported suspicions that one company, Covidien, had acquired another, Newport, to “prevent it from building cheaper products that would undermine Covidien’s profits from its existing ventilator business”, despite the fact that the Newport ventilator was developed with public funding.

As knowledge has been subdivided into separate property claims, we have seen the rise of patent thickets – dense webs of overlapping intellectual property rights claims that a company must use to actually commercialise a new invention. In this context, greater intellectual property rights lead to fewer useful health products.

A recent article showed that while key technological advancements for mRNA vaccines were invented in several academic labs or small biotech companies and then licensed to larger companies, the intellectual property rights owned by or assigned to those larger companies may impede future development of the technology.

Tight intellectual property rights are also counterproductive from a broader economic perspective. Several economists argue that intellectual monopoly capitalism produces economic crisis and stagnation. American scholar H Mark Schwartz has demonstrated that firms based on intellectual property rights have a lower marginal propensity to invest.

The monopolisation of socially produced knowledge by intellectual property rights produces hierarchical relations among firms and between capital and labour, exacerbating inequality and creating a situation where a handful of firms capture the lion’s share of global profits.

It should be noted that IPRs have exacerbated structural global polarisation. While production takes place in the South in exchange for poor wages and accompanied by environmental degradation, transnational corporations whose headquarters are mostly in the North (or in tax havens) extract monopoly rent through IPRs out of value-added that is created in the South. What is new this time is that some historically technologically-advanced Western European countries have been locked out of the “fourth industrial revolution” – advancing information and communication technologies – partially due to IPRs.

Finally, there exists other mechanisms, including prizes and government supported research, that reward invention and disseminate knowledge while avoiding the creation of monopoly power.